int a = 5;

In a recent interview, I was asked this question:

Consider this line of code:

int a = 5;Explain it’s inner working.

To a person like me, who had prepared to be asked questions on DSA, OOPS, DBMS and OS, seeing a question like this was certainly not in my wildest expectations. Although I was able to give a layman answer on how it would work, after the interview ended it evoked a curiosity in me to explore how the computer actually handles this. The fact that this was a line of code I had probably written thousands of times, yet I had not fully understood what happens under the hood was something I did not like, hence I decided to write this blog to document my learning as well as share it with others.

Alright, we have this line of code. Staring at this line of code even for a day will not lead us to any answer, but the computer does understand what to do when we give this line of code right? Well, before this line of code is given to the computer, it is first converted assembly, so let’s look at what kind of assembly code we get from it.

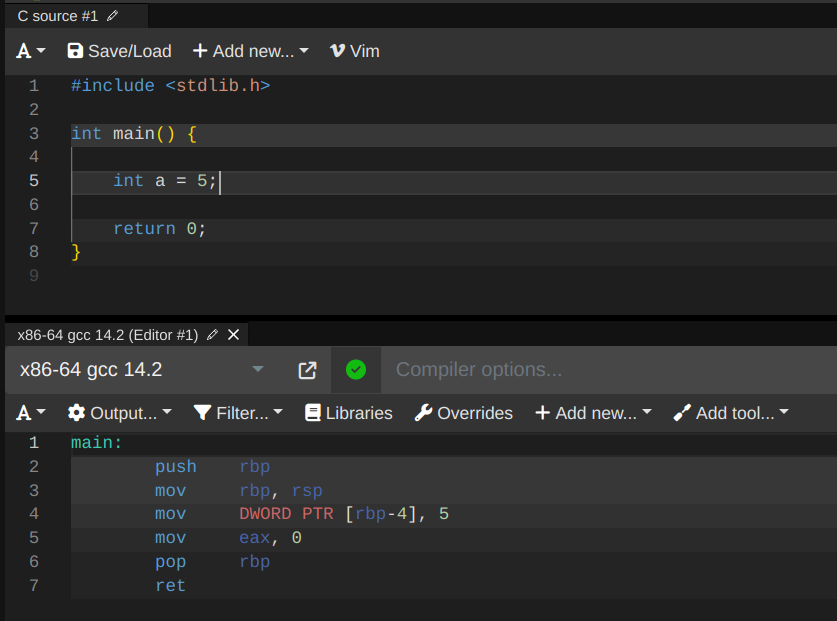

Let’s use the Godbolt compiler explorer for this task.

Bam! This small code seems to dump many scary lines of assembly at us, let us go through each of it line by line. First, let us have a small primer on assembly, so that we can try to decode the meaning of the instructions.

Each assembly instruction is usually one of the following type1:

INS

INS DEST

INS DEST, SRC

INS DEST, SRC, EXTRA

For example, the MOV instruction is of the 3rd type, where we specify the address of the SRC, and it moves the value present in that address to the address given in DEST.

We also need to have some knowledge about registers. Registers can be basically thought of as variables, which are in predefined memory regions which are the “closest” and most easily accessible by the processor. There are many registers available to us, however the only ones that concern us now are EAX, ESP, EBP. Note that whenever write the name of the register, we mean the value in it, however if it is enclosed in [] brackets then we are referencing the value located in that register.

Now what arcane meanings and full forms do these have? Let’s see.

EAX stands for Extended Accumulator Register.

Extended, indicating that this was a extended 32 bit register instead of the original 16 bit AX register.

Accumulator, because it is the primary register used in arithmetic operations.

X, because AX itself is a pair of smaller 8 bit registers known as AL and AH.

EBP stands for Extended Base Pointer and ESP stands for Extended Stack Pointer. In the code that we wrote above, we can see registers such as RBP and RSP. In fact EBP and ESP are the 32 bit version of RBP and RSP, and we will use them interchangeably here, since the context is already understood.

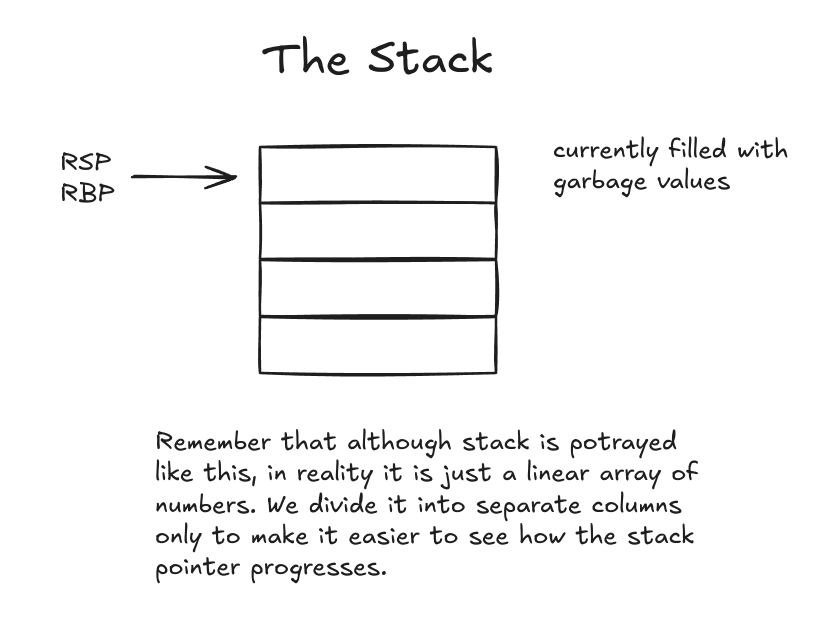

We now have encountered one of the big guns in the scene of process memory management, the Stack. The Stack is the one which overflows your non-base-case-handled recursive calls.

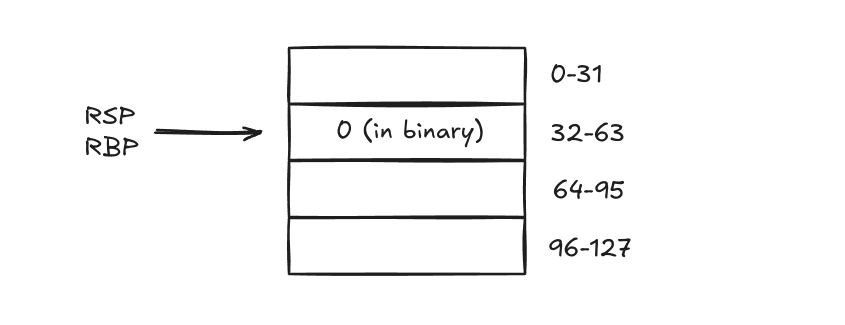

The Stack is a data structure, which allows you to add values only at one end, and allows you to remove only the top value (which is at the same end). Imagine a person carrying a “stack” of dining plates. He can only add plates at the top (or else it would fall down and make a mess) and he can only remove the plates at the top. The stack in our program also works in a similar way, except for a small quirk that it is actually inverted, in the sense that it grows downward. Downward here means that as the stack grows, the magnitude of the address of the top of stack decreases.

Now that you know what a stack is, let’s see what EBP and ESP are.

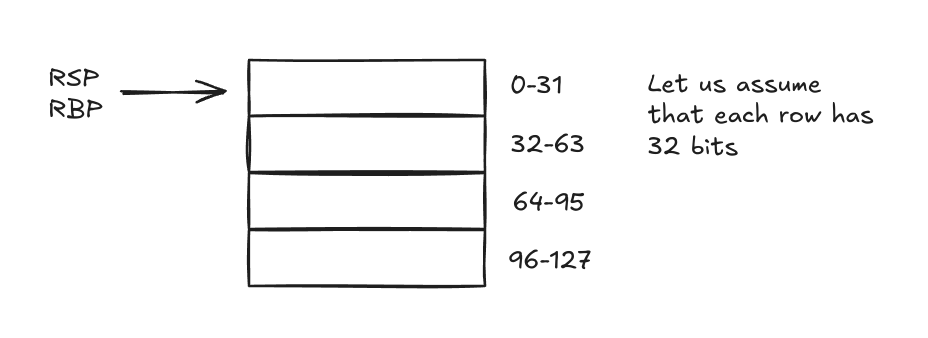

EBP is the pointer which points to the base of the current stack “frame”. A stack frame (which can very in size) can be thought of as a range of addresses on the stack which contains memory space for each function call to store some variables or data, and is no longer valid after the function finishes. The EBP register is also used when we are finding out the addresses of the function arguments, which are located at a fixed offset to it.

ESP is the pointer which points to the top of stack. It is used when we want to push values to the stack.

If you want to know more about assembly level programming, check this out.

Alright. Now that we know how the stack works, let us go back to the code and understand it line by line.

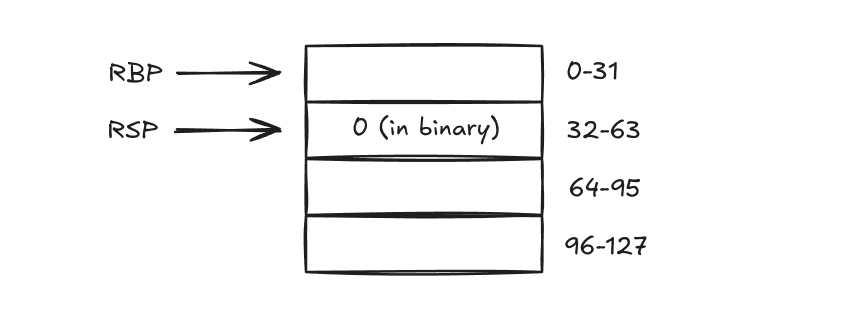

push rbp. This line tells to push the current value of the rbp register to the top of the stack. Anytime we need to create a new stack frame, this instruction is performed, in order to save the address of the RBP of the current stack frame. This is required since after the current function call we need to set it back to the previous stack frame’s base address. This also means that the value of RSP is automatically incremented to point to the new stack top.

mov rbp, rspcopies the value of RSP register, and puts it into RBP register, so that both of them have the same address. This new address will be the Base pointer for the new stack frame being created for the current function call, which is theint main()function call here.

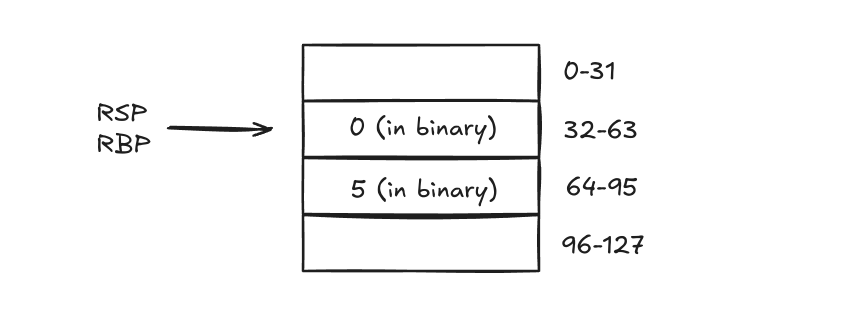

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 5: This instruction asks to move the value5to the address given by[rbp-4]. Notice that since the stack grows downward, we need to subtract the address in order to get the address of the next top element of the stack. The keywordDWORDhere tells us that it is a 32 bit data type, (and is also the reason we are subtracting 4, since int is 4 bytes) andQWORDwould be used instead, if it was 64 bit.

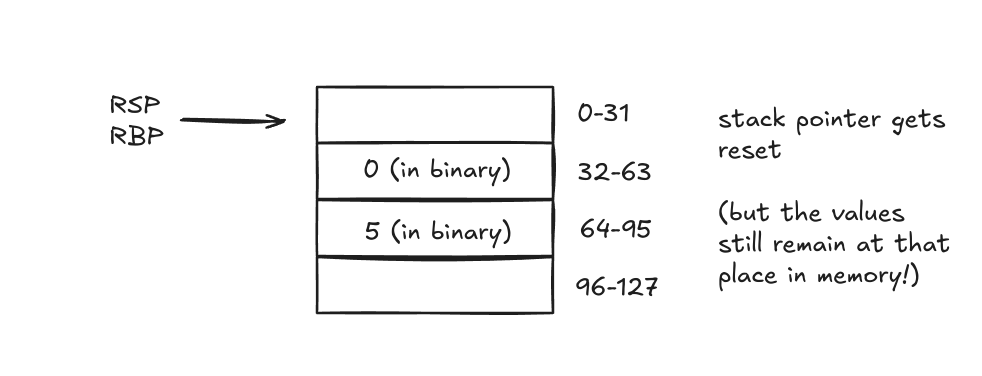

mov eax, 0another thing you need to know, is that whatever the value the function is returning, must always be in the eax register. Also, during the lifetime of a function, it may change the values of any register, but before it exits, it must set all the other registers except EAX to whatever value they had previously, before the function was called. Since we need to return the value 0, we assign the value 0 to the eax register.ret: this exits the function and sets control flow to the place where the function was called. This destroys the topmost stack frame by undoing the operations that happened in this function call.

Phew! so much going on behind the scenes in just a single line of code. We may certainly now ask, okay, but what is happening behind the scenes of command mov DWORD PTR [..], 5? For that we will need to go one more layer deeper. But the gist of it is that Assembly Instructions form an almost one-one correspondance with the op codes present on the processor, and the way these op codes are implemented on the processor is by hard coding the logic gates to get the required work done. It is hard to even imagine the scale of this, when even a usual processor nowadays has 10B transistors. The machine code is processed in a fetch decode execute cycles, where the instruction is fetched, decoded and then executed. We will not be going about that in this post.

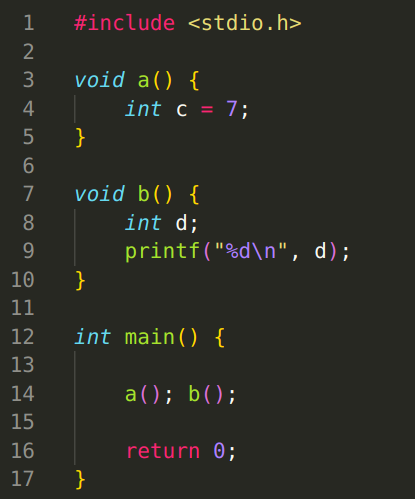

In order to test your understanding of this concept, try to predict the output of this program.

I hope that this blog was just as educational and interesting to you as it was to me. See ya around!

Thanks to Siddharth Bhat for proof-reading and providing suggestions for this post.

— Aug 13, 2024

Search

Made with ❤ and at Earth.